Lower speed limits do not translate into reduced road fatalities despite what authorities would have you believe.

This is the view of Rob Handfield-Jones, road safety expert and managing director of advance driver training company Driving.co.za.

In 2022, the Road Traffic Management Corporation (RTMC) proposed slashing speed limits in an effort to address the scourge of road deaths in the country.

At the time, it noted that a process was underway to reduce urban speed limits from 60km/h to 50km/h, and freeway speed limits from 120km/h to 110km/h.

It said these suggested changes were based on recommendations by the United Nations’ road council, of which South Africa is a member, which said countries with high road fatalities should consider slashing speed limits by 10km/h.

Handfield-Jones told MyBroadband that the fixation on speed limits is rooted in the fact that it is a significant income generator for the authorities, and that it has nothing to do with improving the safety of the roads.

Speed cameras are easy money

“In 1998, South Africa had its safest year in history on our roads despite speed limits which were, on many roads, considerably higher than now,” said Handfield-Jones.

“Speed only gets airtime because it is associated with motor racing and danger, but the irony is that back in 2006 — the last year in which South Africa had credible traffic statistics — a South African racing driver was statistically twice as likely to die in their road car than in their racing car.”

He said that the RTMC, the biggest proponent of speed cap adjustments, has disregarded government’s own research on the efficacy of lower limits.

Referencing a 2003 study of contributory factors to fatal crashes, the expert said that only 7.9% of fatal car accidents listed speed as a contributing factor.

“In other words, 92.1% didn’t — and that’s fatal crashes,” said Handfield-Jones.

“Extend the study to include all crashes and speed would fade into insignificance compared to driver errors like incorrect following distance or insufficient awareness before manoeuvering.”

Several years ago government revised speed limits for public transport vehicles from 120km/h to 100km/h to enhance safety, however, this had nowhere near the intended outcome.

“In fact, four years after the change, the bus occupant fatality rate — as reported by the RTMC — rose by nearly 30% in a single year from 2005 to 2006!” said Handfield-Jones.

In 2021 the RTMC commissioned a more comprehensive study into the effect speed limits have on road fatalities, which Handfield-Jones labeled “almost comedic.”

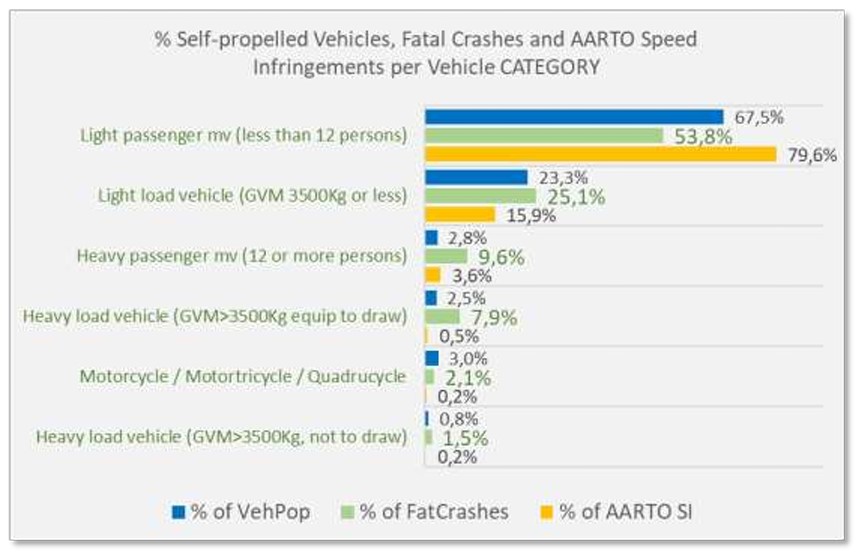

“For example, on page 16, the document includes a graph that accidentally demonstrates an inverse correlation between speeding infringements and fatal crashes for almost all vehicle types, undermining the entire thrust of their argument that more speed prosecution was needed,” he said.

Low speeds are far more dangerous than people realise, said Handfield-Jones.

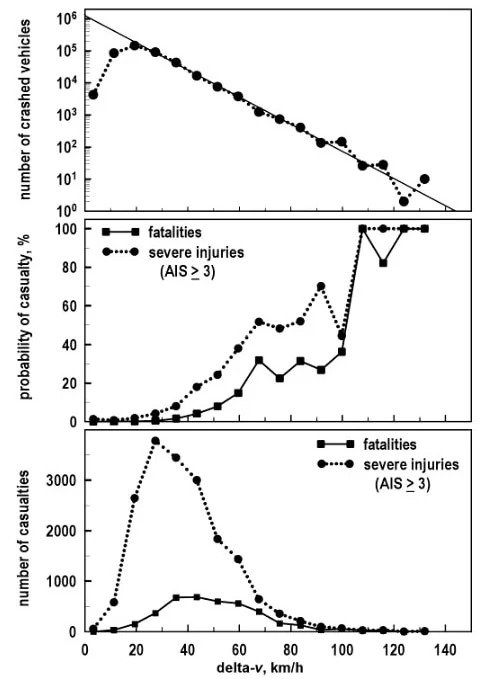

In a 2004 book titled Traffic Safety by Leonard Evans, the author wrote that the median change in velocity (delta-v) at which most vehicle occupants are killed is just 39km/h.

“This research was a primary driver of the global move towards lower urban speed limits, although improved crashworthiness of modern vehicles has played a large part in reducing urban fatality rates,” said Handfield-Jones.

“But a crash with a delta-V over 115km/h is uniformly fatal, so it’s a moot point whether one hits a bridge at 120km/h, nice and legally, or at 140km/h (shock-horror, a reckless speedster!). You’re stone dead in both cases.”

Throwing gasoline on the fire, he said a study by BMW discovered that while the average speed on German Autobahns rose from 115km/h to 124km/h between 1977 and 1994, the fatality rate dropped by 56%.

As such, driver behaviour is the main cause of road deaths, not speed control, said Handfield-Jones.

“The only reason speed continues to suck oxygen from the road safety debate is because it’s misunderstood by most people, but easy to measure and amazingly profitable,” he said.

“Some municipalities derive over 50% of their revenue from traffic fines, almost all of which are for speeding.”

Roughly 15 years ago, data presented at an Institute of Licensing Officers conference revealed that in the three months between 12 February 2009 and 8 May 2009, the Johannesburg metro issued 1,011,084 infringement notices.

These were classified as follows:

- 98.94% for speeding

- 0.57% for disobeying road traffic signs

- 0.24% for disobeying the rules of the road

- 0.08% in connection with fitness of vehicles

- 0.07% for learners and drivers licenses

- 0.05% for registration and licensing of vehicles

- 0.03% for professional driving permits

- 0.01% for passenger carrying vehicles

“Alcohol and driving did not even merit a mention, despite repeated National Injury Mortality Surveillance System studies showing that nearly 58% of all drivers killed in crashes were under the influence,” said Handfield-Jones.

Other experts believe that this 58% statistic doesn’t reflect reality and that the true figure is much higher.

Be that as it may, Handfield-Jones said that prosecuting drunk drivers is hard and expensive, which is why it’s not as frequently discussed by the powers that be as speed limit changes.

“Speed cameras are easy money,” he concluded.